Wes Anderson`s films are immediately recognizable. His symmetrical compositions, pastel color palettes, deadpan humor, and intricate set designs have carved out a unique niche in modern cinema. Viewers are often drawn to the meticulous visual storytelling, the quirky characters, and the melancholic undertones that define his distinct cinematic universe. Yet, beyond the iconic aesthetics, there`s another often-overlooked, yet equally deliberate, element that contributes significantly to his narrative tapestry: food.

Far from being mere background props or fleeting details, the meals, snacks, and beverages in an Anderson film are meticulously chosen narrative devices. They don`t just fill a table; they reveal character, symbolize social status, propel plot points, and even serve as poignant markers of transformation. It`s as if Anderson, with a chef`s precision, understands that the way a character eats, what they eat, or even what they refuse to eat, speaks volumes without uttering a single word.

- The Andersonian Culinary Code: More Than Just a Meal

- Sweet Deception and Shared Stories in The Grand Budapest Hotel

- From Scraps to Splendor in Fantastic Mr. Fox

- A Bite of Society: Isle of Dogs

- Palate of Power and Irony in The French Dispatch

- Simple Sustenance, Profound Connection in Moonrise Kingdom

- The Last Bite: Savoring Anderson`s Artistry

The Andersonian Culinary Code: More Than Just a Meal

In Anderson`s world, food operates on several fascinating levels:

- Contrast and Class: A stark difference in meals often highlights societal divides, contrasting the opulent lives of the privileged with the humble or desperate existence of others.

- Character Revelation: A character`s choice of food, their dining etiquette (or lack thereof), or their reaction to a meal can be a subtle yet profound window into their personality, values, and even their moral compass.

- Plot Progression & Symbolism: Food can be a catalyst for events, a hiding place for secrets, or a symbolic representation of a turning point in a character`s journey.

- Emotional Resonance: Simple shared meals can forge bonds, while elaborate feasts might underscore a dangerous new reality or a fleeting moment of joy.

Let`s savor some prime examples from Anderson`s delectable filmography, where every bite tells a story.

Sweet Deception and Shared Stories in The Grand Budapest Hotel

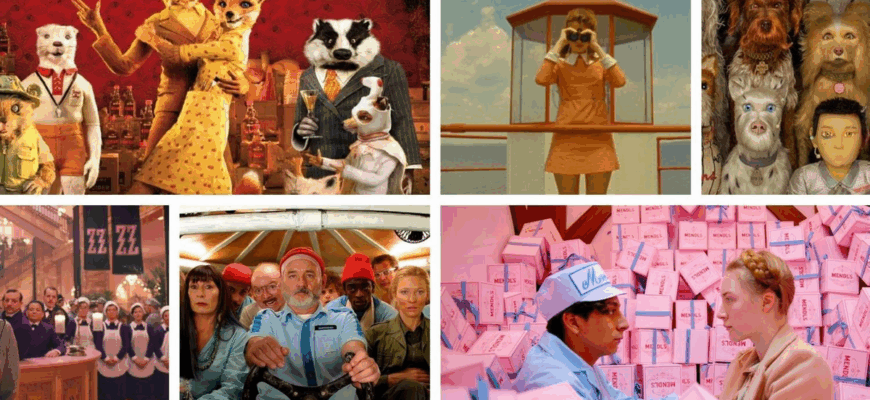

Perhaps no food item is as synonymous with Wes Anderson as the exquisite Mendl`s pastries from The Grand Budapest Hotel. These impeccably stacked, cream-filled choux pastry towers, adorned with delicate ribbons, are more than just a sweet treat; they are a cultural touchstone within the Republic of Zubrowka.

Their significance is multifaceted: they represent artistry, a source of local pride, and even a form of universal currency. When the formidable prison guards, typically ruthless in their inspections, are faced with a box of Mendl`s, their stern demeanor softens. This subtle shift allows the pastries to become an ingenious conduit for smuggling escape tools – a testament to their almost mythical status. The hand that would ordinarily “halve and skewer” any other package simply cannot bring itself to desecrate such a masterpiece. It`s a deliciously ironic subversion of authority, all thanks to a perfect confection.

Further, the entire narrative of the film is framed around a meal. An older Zero Moustafa recounts his youthful adventures over a lavish dinner of roast duck with olives, rabbit, Pouilly-Jouvet, and a bottle of brut. His meticulous, almost performative, order — including a “split of the brut” for the narrator — reveals a character who, despite his humble beginnings, has fully embraced the grandiosity and refined tastes of his late mentor, M. Gustave. The modest “split” of champagne for a boy from a war-torn land underscores his journey from an impoverished lobby boy to the owner of a grand hotel, sharing a taste of what was once an unattainable luxury.

From Scraps to Splendor in Fantastic Mr. Fox

In Fantastic Mr. Fox, the journey of the titular character is vividly marked by the food consumed (or coveted). At the outset, Mr. Fox and his family live a somewhat impoverished existence, symbolized by the infamous moldy toast Mr. Fox devours with gusto. This meager breakfast underscores their simple, albeit happy, life in a cramped hole, a direct contrast to the opulent farm produce he yearns to steal. It`s the starting point, the humble “before” in his transformative arc.

His audacious heists lead to a climactic, almost mythical grand feast. This lavish spread, procured at great risk from the farmers, represents both the apex of Mr. Fox`s cunning and the perilous consequences of his ambition. Badgers, opossums, foxes, and rabbits gather for an unprecedented banquet, a moment of shared, if dangerous, triumph. The irony, of course, is that while they feast below, their world above is under siege, threatened by the very farmers whose bounty they are now enjoying. The contrast between the moldy toast and the lavish spread perfectly encapsulates the film`s themes of ambition, risk, and the definition of happiness.

A Bite of Society: Isle of Dogs

Isle of Dogs uses food to underscore social hierarchy and the harsh realities of exile. When the dogs are unceremoniously deported to Trash Island, their pampered lives abruptly end. Suddenly, they are forced to scavenge for maggot-ridden scraps, moldy rice, and banana peels – a stark, unappetizing contrast to the gourmet meals they once enjoyed. This grim diet highlights their suffering and the dehumanizing (or rather, “dedogifying”) conditions imposed upon them. It`s a raw, visceral depiction of their new, brutal existence.

Conversely, back on the mainland, the insidious corruption manifests in a chilling culinary act. A principled scientist, Professor Watanabe, is targeted with a meticulously prepared luxury sushi set where the traditional wasabi is replaced with a potent poison. The scene is a masterclass in Andersonian detail: the serene precision of the sushi chef, the vibrant colors of the fresh fish, crab, and octopus, all juxtaposed with the sinister act of donning vinyl gloves to administer the deadly agent. It’s a chilling reminder that evil can wear an elegant disguise, transforming an art form into a weapon.

Palate of Power and Irony in The French Dispatch

The French Dispatch, a triptych of stories, also features food as a conduit for character and commentary, particularly in the segment “Revisions to an Inventory of Anatole`s Finances.” Here, the film delves into the world of the wealthy and their peculiar culinary habits.

The character of Anatole, a cunning financier, regularly dines on pigeons, an aristocratic delicacy. His request to give a “slightly burnt” pigeon to his tutor, while keeping the “better” one for himself (despite both appearing identical), speaks volumes about his subtle contempt for others and his self-serving nature. Similarly, his solitary enjoyment of snails—another expensive dish that no one else at the table touches—further solidifies his image as a man of refined (or perhaps just ostentatious) tastes, completely isolated in his indulgence.

In a scene involving negotiations with nightclub owner Marcel Bob, Anderson offers a delightful piece of culinary irony. Bob extends a “warm” welcome with a sweet cocktail adorned with a cherry, followed by the main course: half-opened cans of sardines for each guest. This bizarre pairing, a mix of sugary sweetness and humble fish, perfectly mirrors Marcel Bob`s volatile personality. He initially rages and attempts to dismiss Anatole, only to suddenly concede and even increase his investment – a man, as the article cleverly puts it, like “ice cream with pickles,” unpredictably sweet and sour.

Simple Sustenance, Profound Connection in Moonrise Kingdom

Even in the coming-of-age tale Moonrise Kingdom, a simple meal becomes a powerful moment of connection. After the young runaways Sam and Suzy are separated, Sam finds himself in the humble kitchen of Captain Sharp, the local sheriff (who also happens to be having an affair with Suzy`s mother).

Over a plate of fried sausages and toast, with Captain Sharp sipping beer and Sam still holding onto his milk, a quiet understanding blossoms. Sharp, seeing the distraught boy, offers him a sip of his beer – a gesture that transcends the age gap. Sam, in a subtle yet profound act of acceptance, pours his remaining milk into an ashtray and takes the offered sip. This shared “adult” drink, in such an unassuming domestic setting, signifies a crucial bridging of their worlds. It`s a beautifully understated scene, entirely characteristic of Anderson, where simple sustenance facilitates a deep, unspoken bond and marks Sam`s tentative step into adulthood.

The Last Bite: Savoring Anderson`s Artistry

Wes Anderson`s films are immersive experiences, each frame brimming with meticulously chosen details. It is precisely this fastidious attention that elevates something as mundane as food into a vital component of his storytelling. From symbolizing wealth and poverty to facilitating prison breaks and cementing emotional bonds, food in Anderson`s universe is never incidental. It`s a carefully crafted ingredient in his unique cinematic recipe, inviting audiences not just to watch, but to truly savor the intricate flavors of his narrative genius. So next time you`re immersed in an Andersonian world, pay closer attention to what`s on the menu – you might just discover a whole new layer of storytelling.